Manet’s work might have invited double takes, troubling one’s sense of the “real,” but his figures are nevertheless proportionate, informed by years of training in the corporeal arithmetic of limbs, shoulders, and cheekbones. The exhibition catalogue is laced with works by men-Manet, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec-as if Morisot still has to prove the steadiness of her hand in relation to what is known to be great.

The bias is systemic: from 1864 to 1900, the heart of the d’Orsay’s chronological purview, only three percent of the works purchased by the French state were made by female artists. More than half of the works in the current exhibition come from private collections. Eighty-five percent of her 423 paintings were in the possession of family members at the time of her death, as if she were a talented amateur with a few sentimental devotees. The Morisot who became known as a fixture of the Parisian gratin, as the go-between for some of the more unsociable Impressionists, obscured Morisot the artist.

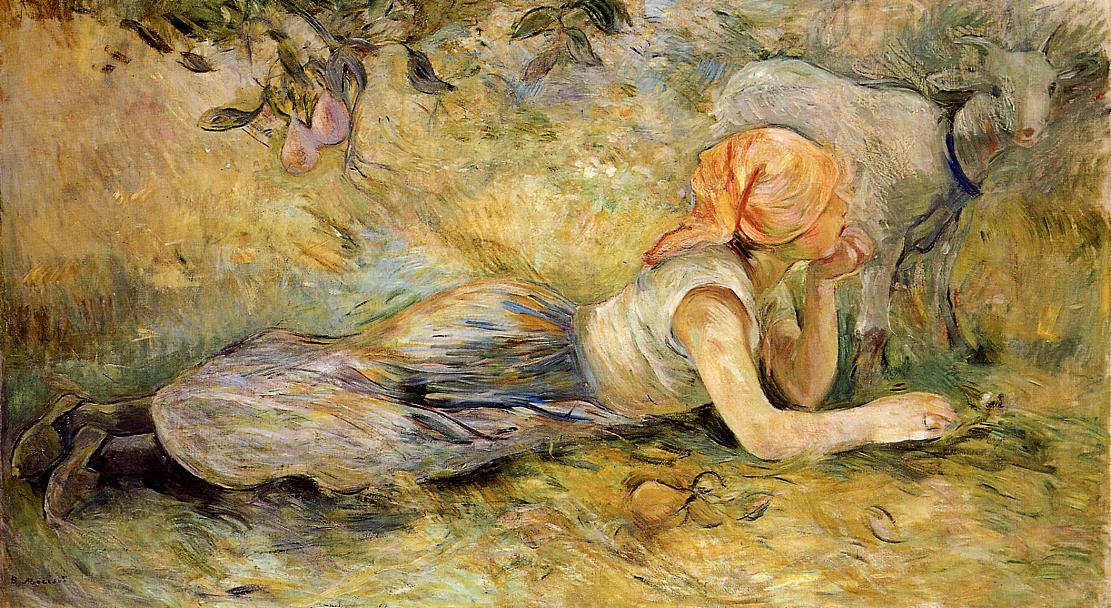

#Berthe morisat taining period artwork windows#

“Their constant activity gave her a foreign air … foreign, meaning strange, but by means of an excessive presence.” Despite being the rumored windows to the soul, eyes do not necessarily give access to the person’s interior. “ lived in her large eyes,” Paul Valéry wrote. The men in her life-and there were some important ones-loved looking at her looking. She starred as Manet’s model in paintings such as The Balcony (1869), where she was the languorous brunette with a half a scowl and a sharp gaze. You’ve already seen Morisot even if you’ve never heard of her. The laurels of universalism are still upheld as a goal here in France, leaving scars in the form of silence-but the winds do seem to be shifting. Many of the French women academics I know, though they consider themselves feminist, refuse to bring feminism into their work for fear of no longer being seen as objective. Since the museum’s opening in 1986, this is the fourth exhibition devoted to a woman artist. The Musée d’Orsay, guardian of the Impressionists, has ignored her through its thirty-year history. Until now, she has been relegated to the provinces and as a side act to Monet at the Marmottan. I visited three weeks after the opening and the crowd was still so dense I had to elbow my way in front of each painting.Īnd yet even this feels like a pittance, given the perennial institutional oversight of Morisot’s legacy. There are three or four canvases to each wall in the small, dark rooms. “Berthe Morisot,” now on at the Musée d’Orsay (after installations in Philadelphia, Dallas, and Quebec), strives to show a complete vision of her oeuvre. “It’s the poets who’ve written the women lovers and ever since we’ve been playing Juliet for ourselves.” She did eventually get married (to Manet’s younger brother, Eugène), but waited until the age of thirty-thirty, when women were more likely to be widowed than plan a wedding.īerthe Morisot © Musée d’Orsay-Patrice Schmidt “People repeat ceaselessly that woman is born to love but that’s what’s hardest for her,” she wrote. Perhaps it was in part a freedom born of being single. But though Berthe shared the same background as her sister, something allowed her to pick up the brush again. She considered giving up painting for good. The next year Berthe destroyed the entirety of her own oeuvre and fell into a creative fallow period. Manet envisioned the Morisot sisters might make their mark in the annals of art as counselors to men in power-by influencing their tastes and sympathies, and convincing them of the worth of outsider artists (such as Manet himself).Įdma gave up her practice when she married in 1869. The possibility that the Morisots might actually become artists did not seem to occur to him. Manet thought the Morisot sisters should “further the cause of painting by marrying académiciens,” members of the jury who selected which works to display at the Académie des Beaux-Arts’s annual salon. He found them “charming” and feared that because they were women, their accomplishments would inevitably go to waste. “It’s annoying they’re not men,” Édouard Manet wrote to fellow artist Henri Fantin-Latour, after meeting Berthe and Edma Morisot, two sisters from the Parisian upper crust who were promising painters. Left: Édouard Manet, Berthe Morisot with Bouquet of Violets, 1872 Right: photo of Berthe Morisot

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)